Unemployment remains high, as well as the deficit of labor in some industries. The vaccine diffusion has imposed as a key element, but wage revision and the work flexibility will be the crucial factors in order to reduce this gap. We offer you our view on a Deloitte’s article, with a profound analysis od the US labor market, as well as some global reflections.

As business restarts in a full swing, an increased number of reports all over the world are stating that companies are struggling to find the necessary staff, especially in the US, UK, Canada, Australia and some European countries.

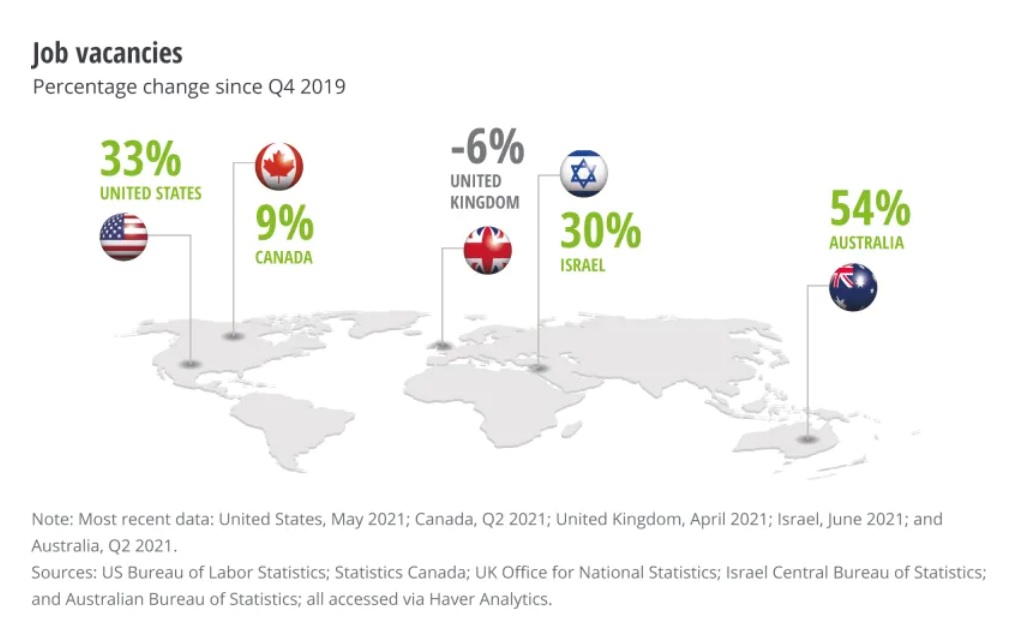

Although it is a periodical phenomenon, it is interesting that this time it coincides with current high unemployment rates. In the U.S., the number of job openings has increased for 33% since the fourth quarter of 2019, yet more than 9 million people remain unemployed. In Canada, the vacancy rate reached its highest level since 2015, while the employment rate remained well below its pre-pandemic peak.

Considering the high number of unemployed labor, companies should find it easier to recruit new workers. However, the pandemic has radically altered workers’ aspirations in terms of desired sectors, working environments and company policies. This makes the previously applied paradigms used for interpreting similar situations, inapplicable.

Between-sector competition

The pandemic has been a disruptive phenomenon for the labor market. In the United States, the unemployment rate rose to a record high of 14.8% in April 2020 before dropping to 5.9% (which is still a high rate!) in June 2021. A survey conducted in March demonstrated that as many as 20% of the U.S. workers changed jobs during the pandemic. The uneven recovery of the economy and the changes in consumer preferences have contributed to the difficulties in finding qualified candidates experienced by employers.

Jobs that could be done remotely continued during the pandemic, while those that required personal interaction largely disappeared. The newly unemployed sought positions in the few industries that were actively hiring, often changing occupations and industries. In the U.S., at least 1.7 million leisure and hospitality workers who lost their jobs since the fourth quarter of 2019 have either found employment in a different industry or chosen to remain inactive, making it much more difficult for employers to find candidates with the required experience. A survey conducted by Deloitte in January of this year showed that two-thirds of the unemployed were "seriously considering changing occupations or industries," and one-third had already begun retraining to do so.

Now that the economy has decisively restarted, the question in the area of personal services (as well as the hospitality sector) is increasing. Consequently, the job openings are increasing too. A the same time, partly thanks to the substantial stimulus of the American government, the manufacturing and technical services sectors have performed relatively well over the past year and a half, which means that they never stopped hiring, and continue in doing so.

A couple of examples: U.S. manufacturing vacancies have more than doubled from the pre-pandemic levels; U.K. manufacturing vacancies are 30 percent higher than they were a year and a half ago; and Canadian professional, scientific, and technical services employment has increased for 33.4 percent. Strong demand for workers is putting these sectors in a competition with each other, while potential candidates have more choices and thus opportunities to rethink their career.

Infection risk and job attractiveness

The increased risk of contracting Covid-19 has made some professions riskier than others, and as a result, companies working in these sectors will find it more difficult to attract labor while maintaining pre-pandemic salary levels. For example, wage rates for food service workers could increase, considering that cooks experienced a 60 percent increase in mortality in 2020 compared to non-pandemic periods. If there will be no adjustments done, it is very likely that the unemployed will be more attracted to low-risk jobs, particularly those that can be done remotely. For some people, the risk of illness represents an obstacle to entering the workforce. A survey conducted in June 2021 found that just over 3 million Americans were unemployed precisely because of the fear of contracting Covid.

In the last two years there has been a change in the geography of the working world too. Although many people have decided to relocate due to the pandemic, most of these moves have occurred over relatively short distances. For example, in the United Kingdom, the average homebuyer search radius increased by just 1 mile (from 9 to 10 miles) compared to 2019. In the U.S., the number of moves to the suburbs rather than metropolitan areas has not varied much, but whereas before the pandemic, suburbanites would have gone to the central business district, today they remain in the suburbs thanks to remote working arrangements. This makes it more complicated to find professionals willing to move to the city.

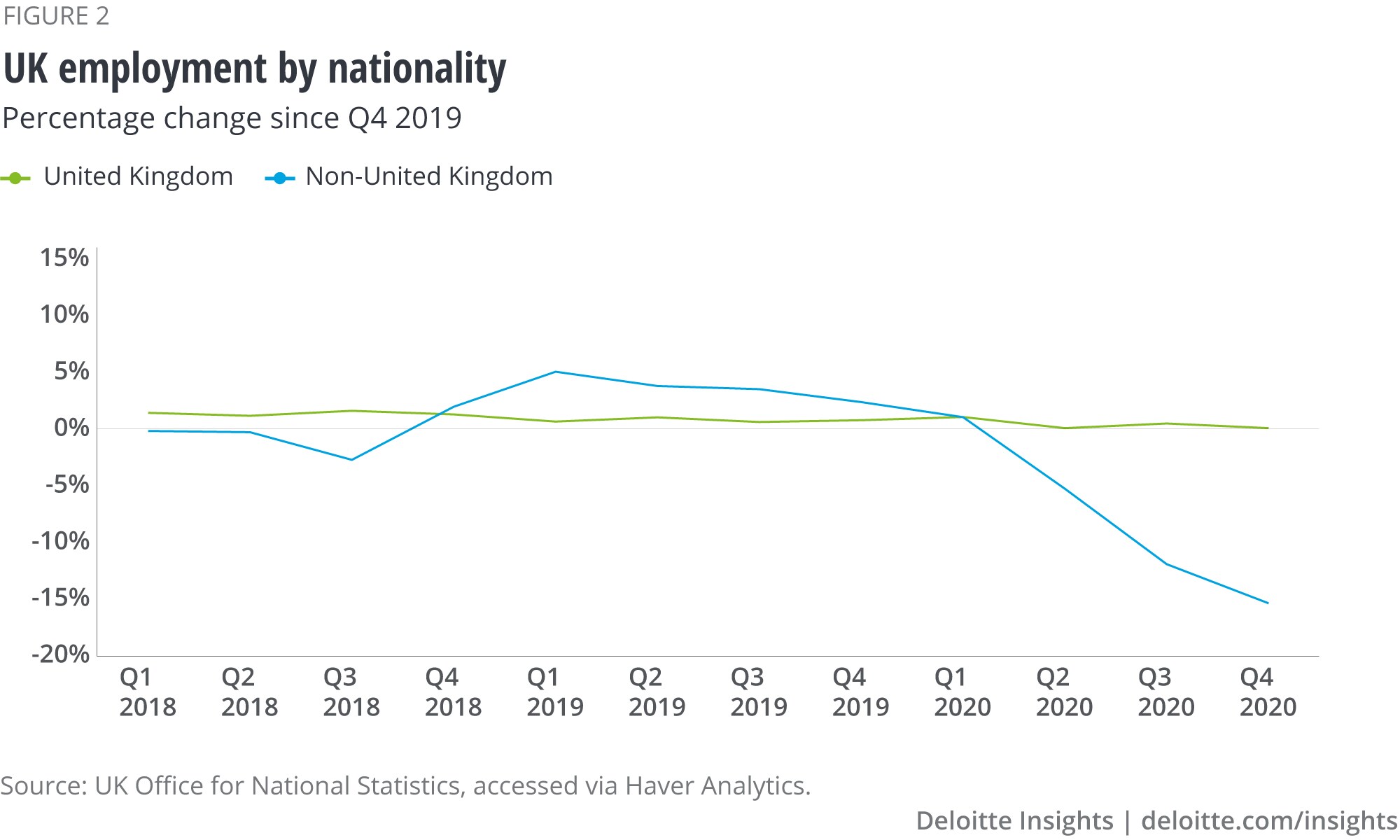

International immigration is another factor that adds to the problems of labor shortages. The U.K. Faces the biggest challenge, where Brexit has significantly limited the ability for EU workers to come to the country. About 1.3 million non-British workers, or about 4 percent of the workforce, had left during the pandemic. To make matters worse, many of these workers were concentrated in a limited number of sectors, such as hospitality and food services, that have only recently begun to reopen and find themselves undertaffed as a consequence.

Other countries are also facing similar challenges, albeit on a smaller scale. In Canada, international migration has declined by nearly 400,000 persons yearly until the first quarter of 2021, which equates to a loss of nearly 2 percent of the workforce. In Australia, the population has declined for the first time in a century due to border closures and immigration restrictions.

Salary revision

The fundemental factor regarding the restart of every sector will be the vaccines difusion. Beyond this fact, Deloitte’s article suggests that as a remedy for workforce shortages – companies should invest in technology, equipmenet and software that can optimize the productivity of the existitng resources.

In that direction, some experimentation in the manufacturing sector in the United States is already yielding excellent results.

Certainly an upward revision of salaries will help attract more candidates. Of course, this will result in reduced profits or higher customer prices, but in many cases it will be the only way forward. At the moment, however, wage growth in some sectors, such as manufacturing, appears low compared to the tension observed in the labor market. For example, there are more manufacturing vacancies in the U.K. than there were before the pandemic, but wage growth has averaged only 1.8 percent over the past two years, which is considerably lower than the growth observed before the pandemic. Similarly, wage growth in Canada's mining and manufacturing sector has been particularly weak, despite labor shortages.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution to the challenges companies are facing in the labor market. The situation may become easier as vaccine uptake increases and therefore some occupations return to a lower level of risk, but it is likely that some of the phenomena triggered by the pandemic are just beginning.